E-Book by Alan F. Alford (www.eridu.co.uk)

Author of 'Gods of the New Millennium', 'The Phoenix Solution' and 'When The Gods Came Down'.

WHERE did we come from? Are we the product of a Divine Creation? Did we evolve through natural selection? Or is there another possible answer?

Introduction

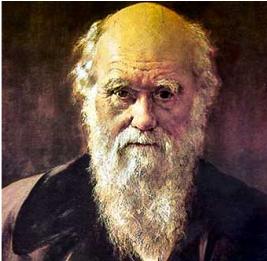

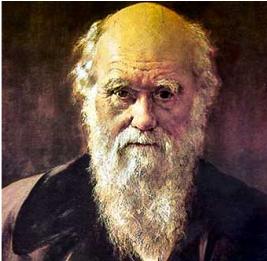

In November 1859, Charles Darwin published a most dangerous idea - that all living things had evolved through a process of natural selection. Although there was almost no mention of mankind in Darwin's treatise, the implications were unavoidable and led to a more radical change in human self-perception than anything before it in recorded history. In one blow, Darwin had relegated us from divinely-created beings to apes - the culmination of evolution by the impersonal mechanism of natural selection.

But are the scientists right in applying the theory of evolution to the strange two-legged hominid known as 'man'? Charles Darwin himself was strangely quiet on this point but his co-discoverer Alfred Wallace was less reluctant to express his views. Wallace himself was adamant that 'some intelligent power has guided or determined the development of man.'

One hundred years of science have failed to prove Alfred Wallace wrong. Anthropologists have failed miserably to produce fossil evidence of man's 'missing link' with the apes and there has been a growing recognition of the complexity of organs such as the human brain. Such are the problems with the application of Darwinism to mankind that Stephen Jay Gould - America's evolutionist laureate - has described human evolution as an 'awesome improbability'.

In Search of the Missing Link

Speciation - the separation of one species into two different species - is defined as the point where two groups within the same species are no longer able to inter-breed. The British scientist Richard Dawkins has described the separation quite poetically as 'the long goodbye'.

The search for the missing link between man and the apes is the search for the earliest hominid - the upright, bipedal ape who waved 'a long goodbye' to his four-legged friends.

I will now attempt to briefly summarise what is known about human evolution.

According to the experts, the rivers of human genes and chimpanzee genes split from a common ancestral source some time between 5 and 7 million years ago, whilst the river of gorilla genes is generally thought to have branched off slightly earlier. In order for this speciation to occur, three populations of common ape ancestors (the future gorillas, chimpanzees and hominids) had to become geographically separated and thereafter subject to genetic drift, influenced by their different environments.

The search for the missing link has turned up a number of fossil contenders, dating from around 4 million years ago, but the picture remains very incomplete and the sample size is too small to draw any statistically valid conclusions. There are, however, three contenders for the prize of the first fully bipedal hominid, all discovered in the East African Rift valley which slashes through Ethiopia, Kenya and Tanzania.

The first contender, discovered in the Afar province of Ethiopia in 1974, is named Lucy, although her more scientific name is Australopithecus Afarensis. Lucy is estimated to have lived between 3.6-3.2 million years ago. Unfortunately her skeleton was only 40 per cent complete and this has resulted in controversy regarding whether she was a true biped and whether in fact 'she' might even have been a 'he'.

The second contender is Australopithecus Ramidus, a 4.4 million year old pygmy chimpanzee-like creature, discovered at Aramis in Ethiopia by Professor Timothy White in 1994. Despite a 70 per cent complete skeleton, it has again not been possible to prove categorically whether it had two or four legs.

The third contender, dated between 4.1-3.9 million years old, is the Australopithecus Anamensis, discovered at Lake Turkana in Kenya by Dr Meave Leakey in August 1995. A shinbone from Anamensis has been used to back up the claim that it walked on two feet.

The evidence of our oldest ancestors is confusing because they do not seem to be closely related to each other. Furthermore, the inexplicable lack of fossil evidence for the preceding 10 million years has made it impossible to confirm the exact separation date of these early hominids from the four-legged apes. It is also important to emphasise that many of these finds have skulls more like chimpanzees than men. They may be the first apes that walked but, as of 4 million years ago, we are still a long way from anything that looked even remotely human.

Moving forward in time, we find evidence of several types of early man which are equally confusing. We have the 1.8 million year old appropriately named Robustus, the 2.5 million year old and more lightly built Africanus , and the 1.5 to 2 million year old Advanced Australopithecus. The latter, as the name suggests, is more man-like than the others and is sometimes referred to as 'near-man' or Homo habilis ('handy man'). It is generally agreed that Homo habilis was the first truly man-like being which could walk efficiently and use very rough stone tools. The fossil evidence does not reveal whether rudimentary speech had developed at this stage.

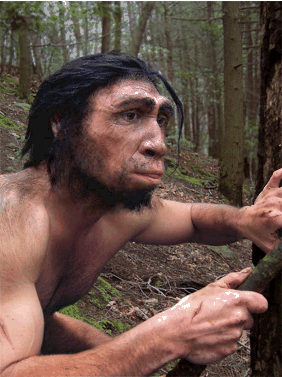

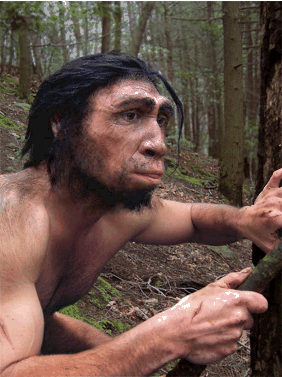

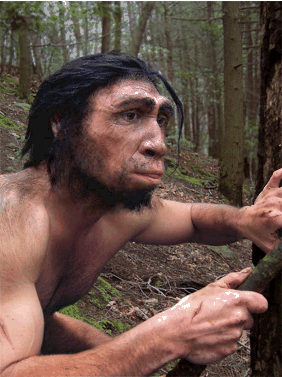

Around 1.5 million years ago Homo erectus appeared on the scene. This hominid had a considerably larger brain-box (cranium) than its predecessors and started to design and use more sophisticated stone tools. A wide spread of fossils indicates that Homo erectus groups left Africa and spread across China, Australasia and Europe between 1,000,000-700,000 years ago but, for unknown reasons, disappeared altogether around 300,000-200,000 years ago. There is little doubt, by a process of elimination, that this is the line from which Homo sapiens descended.

The missing link, however, remains a mystery. In 1995, The Sunday Times summarised the evolutionary evidence as follows:

The scientists themselves are confused. A series of recent discoveries has forced them to tear up the simplistic charts on which they blithely used to draw linkages... the classic family tree delineating man's descent from the apes, familiar to us at school, has given way to the concept of genetic islands. The bridgework between them is anyone's guess.

As to the various contenders speculated as mankind's ancestor, The Sunday Times stated:

Their relationships to one another remain clouded in mystery and nobody has conclusively identified any of them as the early hominid that gave rise to Homo sapiens.

In summary, the evidence discovered to date is so sparse that a few more sensational finds will still leave the scientists clutching at straws. Consequently mankind's evolutionary history is likely to remain shrouded in mystery for the foreseeable future.

The Miracle of Man

Today, four out of ten Americans find it difficult to believe that humans are related to the apes. Why is this so? Compare yourself to a chimpanzee. Man is intelligent, naked and highly sexual - a species apart from his alleged primate relatives.

This may be an intuitive observation but it is actually supported by scientific study. In 1911, the anthropologist Sir Arthur Keith listed the anatomical characteristics peculiar to each of the primate species, calling them 'generic characters' which set each apart from the others. His results were as follows: gorilla 75; chimpanzee 109; orang-utan 113; gibbon 116; man 312. Keith thus showed scientifically that mankind was nearly three times more distinctive than any other ape.

Another scientist to take this approach was the British zoologist Desmond Morris. In his book, The Naked Ape, Desmond Morris highlighted the amazing mystery of mankind's 'missing hair':

Functionally, we are stark naked and our skin is fully exposed to the outside world. This state of affairs still has to be explained, regardless of how many tiny hairs we can count under a magnifying lens.

Desmond Morris contrasted Homo sapiens with 4,237 species of mammals, the vast majority of which were hairy or partly haired. The only non-hairy species were those which lived underground (and thus kept warm without hair), species which were aquatic (and benefited from streamlining), and armoured species such as the armadillo (where hair would clearly be superfluous). Morris commented:

The naked ape [man] stands alone, marked off by his nudity from all the thousands of hairy, shaggy or furry land-dwelling mammalian species... if the hair has to go, then clearly there must be a powerful reason for abolishing it.

Darwinism has yet to produce a satisfactory answer as to how and why man lost his hair. Many imaginative theories have been suggested, but so far no-one has come up with a really acceptable explanation. The one conclusion that can perhaps be drawn, based on the principle of gradiented change, is that man spent a long time evolving, either in a very hot environment or in water.

Another unique feature of mankind may provide us with a clue to the loss of body hair. That feature is sexuality. The subject was covered in juicy detail by Desmond Morris, who highlighted unique human features such as extended foreplay, extended copulation and the orgasm. One particular anomaly is that the human female is always 'in heat', yet she can only conceive for a few days each month.

As another scientist, Jared Diamond, has pointed out, this is an evolutionary enigma that cannot be explained by natural selection:

The most hotly debated problem in the evolution of human reproduction is to explain why we nevertheless ended up with concealed ovulation, and what good all our mistimed copulations do us.

Many scientists have commented also on the anomaly of the male penis, which is by far the largest erect penis of any living primate. The geneticist Steve Jones has noted it as a mystery which is 'unanswered by science', a point which is echoed by Jared Diamond:

... we descend to a glaring failure: the inability of twentieth-century science to formulate an adequate Theory of Penis Length... astonishing as it seems, important functions of the human penis remain obscure.

Desmond Morris described man as 'the sexiest primate alive', but why did evolution grant us such a bountiful gift? The whole human body seems to be perfectly designed for sexual excitement and pair bonding. Morris saw elements of this plan in the enlarged breasts of the female, the sensitive ear lobes and lips, and a vaginal angle that encouraged intimate face to face copulation. He also highlighted our abundance of scent-producing glands, our unique facial mobility and our unique ability to produce copious tears - all features which strengthened the exclusive emotional pair-bonding between male and female.

This grand design could not be imagined unless humans also lost their shaggy coat of hair and so it might seem that the mystery of the missing hair is solved. Unfortunately, it is not that simple, for evolution does not set about achieving grand designs. The Darwinists are strangely silent on what incremental steps were involved, but however it happened it should have taken a long, long time.

There are three other interesting anomalies of 'the naked ape' which are also worthy of note. The first is the appalling ineptitude of the human skin to repair itself. In the context of a move to the open savannah, where bipedal man became a vulnerable target, and in the context of a gradual loss of protective hair, it seems inconceivable that the human skin should have become so fragile relative to our primate cousins.

The second anomaly is the unique lack of penis bone in the male. This is in complete contrast to other mammals, which use the penis bone to copulate at short notice. The deselection of this vital bone would have jeopardised the existence of the human species unless it took place against the background of a long and peaceful environment.

The third anomaly is our eating habits. Whereas most animals will swallow their food instantaneously, we take the luxury of six whole seconds to transport our food from mouth to stomach. This again suggests a long period of peaceful evolution.

The question, which arises, is where this long and peaceful evolution is supposed to have taken place, because it certainly does not fit the scenario which is presented for Homo sapiens. Nor have Darwinists explained adequately how the major changes in human anatomy were achieved in a time frame of only 6 million years...

What does the fossil record tell us about our evolving brain capabilities? The data varies considerably and must be treated with care (since the sample sizes are limited), but the following is a rough guide.

The early hominid Afarensis had around 500cc and Habilis/Australopithecus had around 700cc. Whilst it is by no means certain that one evolved from the other, it is possible to see in these figures the evolutionary effects over two million years of the hominid's new environment.

As we move forward in time to 1.5 million years ago, we find a sudden leap in the cranial capacity of Homo erectus to around 900-1000cc. If we assume, as most anthropologists do, that this was accompanied by an increase in intelligence, it represents a most unlikely macromutation. Alternatively, we might explain this anomaly by viewing erectus as a separate species whose ancestors have not yet been found due to the poor fossil records.

Finally, after surviving 1.2 to 1.3 million years without any apparent change, and having successfully spread out of Africa to China, Australasia and Europe, something extraordinary happened to the Homo erectus hominid. Perhaps due to climatic changes, his population began to dwindle until he eventually died out. And yet, while most Homo erectus were dying, one managed to suddenly transform itself into Homo sapiens , with a vast increase in cranial capacity from 950cc to 1450cc.

Human evolution thus appears like an hourglass, with a narrowing population of Homo erectus leading to possibly one single mutant, whose improved genes emerged into a new era of unprecedented progress. The transformation from failure to success is startling. It is widely accepted that we are the descendants of Homo erectus (who else was there to descend from?) but the sudden changeover defies all known laws of evolution. Hence Stephen Jay Gould's comment about the 'awesome improbability of human evolution'.

Why has Homo sapiens developed intelligence and self-awareness whilst his ape cousins have spent the last 6 million years in evolutionary stagnation? Why has no other creature in the animal kingdom developed an advanced level of intelligence?

The conventional answer is that we stood up, thereby releasing our two arms, and began to use tools. This breakthrough accelerated our learning through a 'feedback' system, which stimulated mental development.

The latest scientific research does confirm that electrochemical processes in the brain can sometimes stimulate the growth of dendrites - the tiny signal receptors which attach to the neurons (nerve cells). Experiments with caged rats have shown greater brain mass developing where the cages are full of toys rather than empty.

But is this answer too simple? The kangaroo, for instance, is extremely dexterous and could have used tools but never did, whilst the animal kingdom is full of species which do use tools but have never become intelligent. Here are some examples. The Egyptian vulture throws stones at ostrich eggs to crack their tough shells. The woodpecker finch in the Galapagos Islands uses twigs or cactus spines in up to five different ways to root out wood-boring insects from rotten trees. The sea otter on the Pacific coast of North America uses a stone as a hammer to dislodge its favourite food, the abalone shellfish, and uses another stone as an anvil to smash open the shellfish.

These are examples of simple tool use, but there is no sign of it leading anywhere. Our nearest relatives, the chimpanzees, also make and use simple tools, but can we really see them evolving intelligence at our level? Why did we acquire a brain which qualifies as 'the most complex object in the known universe', whilst the chimpanzees did not?

Understanding Darwinism

In order to throw down the gauntlet to the evolutionists, it is essential to conduct the fight in their own territory. A basic understanding of state-of-the-art Darwinian thinking is therefore essential.

When Darwin first put forward his theory of evolution by natural selection, he could not possibly have known the mechanism by which it occurred. It was almost one hundred years later, in 1953, that James Watson and Francis Crick discovered that mechanism to be DNA and genetic inheritance. Watson and Crick were the scientists who discovered the double helix structure of the DNA molecule - the chemical which encodes genetic information. Our schoolchildren now understand that every cell in the body contains 23 pairs of chromosomes, onto which are fixed approximately 100,000 genes making up what is known as the human genome. The information contained in these genes is sometimes switched on, to be read, sometimes not, depending on the cell and the tissue (muscle, bone or whatever) which is required to be produced. We also now understand the rules of genetic inheritance, the basic principle of which is that half of the mother's and half of the father's genes are recombined.

How does genetics help us to understand Darwinism? It is now understood that our genes undergo random mutations as they are passed through the generations. Some of these mutations will be bad, some good. Any mutation which gives a survival advantage to the species will by and large, over many many generations, spread through the whole population. This accords with the Darwinian idea of natural selection - a continuous struggle for existence in which those organisms best fitted to their environment are the most likely to survive. By surviving, an organism's genes are more likely, statistically, to be carried into later generations through the process of sexual reproduction.

A common misconception with natural selection is that genes will directly improve in response to their environment, causing optimal adjustments of the organism. It is now accepted that such adaptations are in fact random mutations which happened to suit the environment and thus survived. In the words of Steve Jones: 'we are the products of evolution, a set of successful mistakes'.

How fast is the process of evolution? The experts all agree with Darwin's basic idea that natural selection is a very slow, continuous process. As one of today's great champions of evolution, Richard Dawkins, has put it: 'nobody thinks that evolution has ever been jumpy enough to invent a whole new fundamental body plan in one step'.

Indeed, the experts think that a big evolutionary jump, known as a macromutation, is extremely unlikely to succeed, since it would probably be harmful to the survival of a species which is already well adapted to its environment.

We are thus left with a process of random genetic drift and the cumulative effects of genetic mutations. But even these minor mutations are thought to be generally harmful. Daniel Dennett neatly illustrates the point by drawing an analogy with a game whereby one tries to improve a classic piece of literature by making a single typographical change. Whilst most changes such as omitted commas or mis-spelled words would have negligible effect, those changes which were visible would in nearly all cases damage the original text. It is rare, though not impossible, for random change to improve the text.

The odds are already stacked against genetic improvement but we must add one further factor. A favourable mutation will only take hold if it occurs in small isolated populations. This was the case on the Galapagos Islands, where Charles Darwin carried out much of his research. Elsewhere, favourable mutations will be lost and diluted within a larger population and scientists admit that the process will be a lot slower.

If the evolution of a species is a time-consuming process, then the separation of one species into two different species must be seen as an even longer process. Richard Dawkins compares the genes of different species to rivers of genes which flow through time for millions of years. The source of all these rivers is the genetic code which is identical in all animals, plants and bacteria that have ever been studied. The body of the organism soon dies but, through sexual reproduction, acts as a mechanism which the genes can use to travel through time. Those genes which work well with their fellow-genes, and which best assist the survival of the bodies through which they pass, will prevail over many generations.

But what causes the river, or species, to divide into two branches? To quote Richard Dawkins:

The details are controversial, but nobody doubts that the most important ingredient is accidental geographical separation.

As unlikely as it may seem, statistically, for a new species to occur, the fact is that there are today approximately 30 million separate species on Earth and it is estimated that a further 3 billion species may have previously existed and died out. One can only believe this in the context of a cataclysmic history of planet Earth - a view which is becoming increasingly common. Today, however, it is impossible to pinpoint a single example of a species which has recently (within the last half a million years) improved by mutation or divided into two species.

With the exception of viruses evolution appears to be an incredibly slow process. Daniel Dennett recently suggested that a time scale of 100,000 years for the emergence of a new animal species would be regarded as 'sudden'. At the other extreme, the humble horseshoe crab has remained virtually unchanged for 200 million years. The consensus is that the normal rate of evolution is somewhere in the middle. The famous biologist Thomas Huxley, for example, stated that:

Large changes [in species] occur over tens of millions of years, while really major ones [macro changes] take a hundred million years or so.

In the absence of fossil evidence, we are dealing with extremely theoretical matters. Nevertheless, modern science has managed, in a number of cases, to provide feasible explanations of how a step-by-step evolutionary process can produce what appears to be a perfect organ or organism. The most celebrated case is a computer-simulated evolution of the eye by Nilsson and Pelger. Starting with a simple photocell, which was allowed to undergo random mutations, Nilsson and Pelger's computer generated a feasible development to full camera eye, whereby a smooth gradient of change occurred with an improvement at each intermediate step.